In the field of art conservation, history is seldom static. “Opinions, authenticity, and judgments about works of art and other historical objects are always in flux,” says Mary MacNaughton ’70, professor of art history and Gabrielle Jungels-Winkler Director of the Ruth Chandler Williamson Gallery. “Art conservation brings together hard evidence, intuition, judgment, and insight gained over a lifetime of looking.”

Scripps is the only undergraduate institution on the West Coast that offers an art conservation major, and the program is one of only a handful in the nation open to undergraduates. With a curriculum modeled on graduate-level study—two years of chemistry, courses in studio art, archaeology, anthropology, and art history, and early, hands-on experience working directly with art conservators—the program produces alums who attend graduate school and enter the profession at high rates.

Working on projects as diverse as preserving heritage sites, piecing together ancient pottery, or analyzing pigment to discern whether a work is authentic, conservators often make discoveries that shine new light on art-historical truths. “I love detective stories and I love sleuthing—working as an art conservator is the real-world application of this,” says MacNaughton.

We asked three Scripps alumnae to describe how they are using their art conservation training to uncover hidden truths about works of art.

Geneva Griswold ’07

Associate Objects Conservator, Seattle Art Museum

One of the highlights of the Seattle Asian Art Museum’s collection is Monk at the Moment of Enlightenment, a 14th-century polychrome wood sculpture. With his expressive face and skyward gaze, this dynamic figure has been a bit of an enigma. His pose has historically been interpreted as signifying a moment of enlightenment; however, new scholarship by Ping Foong, the museum’s Foster Foundation Curator of Chinese Art, has sought to identify the monk as a Taming Dragon Luohan, based in part on inked characters that are partially legible on his back.

My role as conservator on this project has been to support curatorial research through the technical study of the artwork’s materials and how they are

put together. Infrared reflectance photography, commonly used to visualize carbon-based underdrawings and faded inscriptions, has confirmed that the rest of the inked characters are lost—not just covered by paint or otherwise obscured.

Sculptures sometimes include consecrated objects, such as a sutra, a bronze mirror, textiles, or other offerings within cavities in the body. Unlike the two empty cavities in the monk’s back, the cavity in his head had never been opened, and it was hoped that objects that could locate his origin lay inside. X-radiography revealed that a material slightly denser than wood was present. Higher-resolution imaging was achieved by a computed tomography scan conducted with help from intern and recent Scripps graduate Milena Carothers ’19, who identified the lumpy, tubular forms attached to the upper corner of the cavity as mud wasp nests.

Thus, the figure remains an enigma: the lack of objects inside his head means that identification will require additional study, including travel to temple sites to view similar sculptures in situ, further characterization of the script on the back (no scholar has previously pursued this text), and an assessment of whether his posture, gaze, and grasp of the drapery relates him to Taming Dragon depictions in other art media (painting or marble, for example). In this way, conservators are well prepared by Scripps’ Core Curriculum to draw connections between diverse areas of study and context.

Monk at the Moment of Enlightenment

14th-century Chinese

Wood with polychrome decorations

41 x 30 x 22 in.

Eugene Fuller Memorial Collection, 36.1

McKenzie Floyd ’12

Associate Curator of Art, Boise Art Museum

Many conservators and museums use expensive methods, such as infrared reflectography, to expose invisible details in works of art. These technologies enable viewers to see more wavelengths in the light spectrum, allowing them to discern aspects of the work—provenance, or the ways in which it’s aged or been altered—that are often impenetrable to the naked eye.

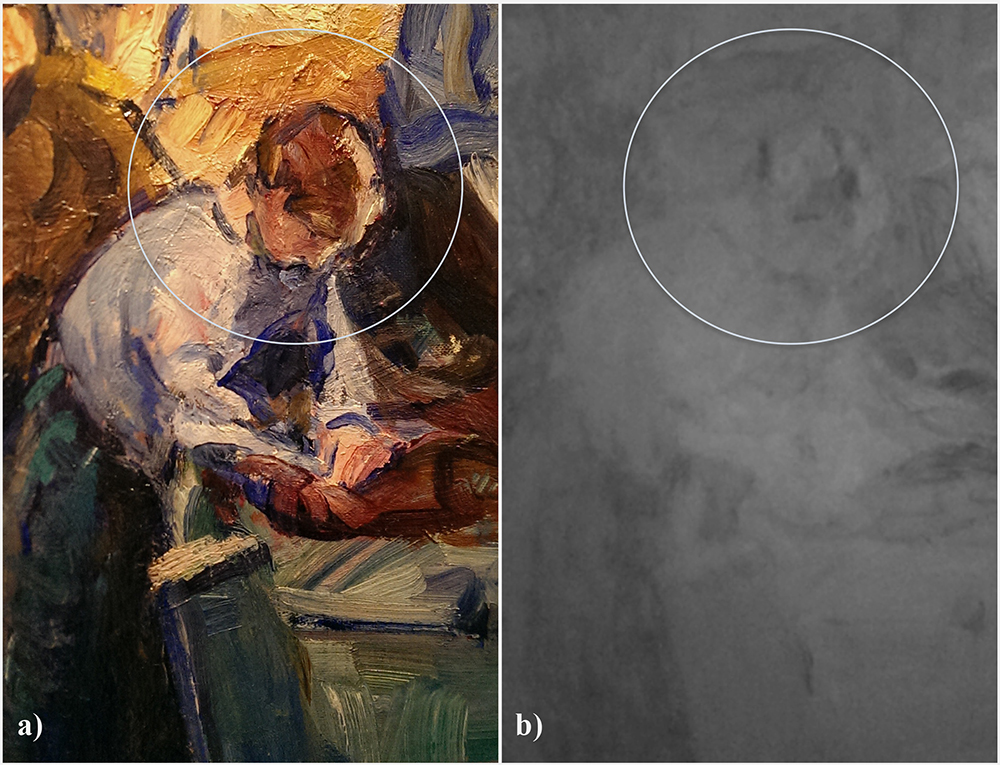

While teaching chemistry at California State University, Monterey Bay, I worked with student researchers on making such methods more accessible to educators and art lovers. Using a smartphone camera, we attached a filter that blocks visible light but allows infrared wavelengths to pass through the lens to show how this simple adaptation of familiar technology can be used to explore the hidden dimensions of art.

One painting we examined using this technology was The Green Boat, St. Tropez by California impressionist E. Charlton Fortune. When observing this work with the human eye, we can only appreciate the final image. But when we looked at the painting through our device, the top layer of the work became transparent, revealing details beneath. In this case, the artist originally drew the fisherman with a hat, but ultimately painted over it.

My goal for this research, which was recently published in the Journal of Chemical Education, was not to replace high-tech methods but to make analysis accessible to individual collectors and small museums. I’m interested in helping people learn more about their own personal collections and the artistic process.

This combination of chemistry and art is originally what drew me to art conservation at Scripps (fun fact: I was the first student in the major!). I grew up around artists but also loved chemistry, so it was a natural choice for me. My art conservation education prepared me for my graduate work in chemistry and museum studies and even applies to my curatorial work at the Boise Art Museum. The interdisciplinary skills students learn in Scripps’ art conservation program are invaluable to a wide range of careers in the arts.

Charlton Fortune

The Green Boat, St. Tropez

1925, detail and infrared image revealing a hidden fisherman’s hat

Oil on canvas

30 x 40 in.

Photo by McKenzie Floyd and Alexa Torres and printed

with permission from the Monterey Museum of Art

Kaela Nurmi ’15

Graduate Fellow in Conservation, Buffalo State College SUNY

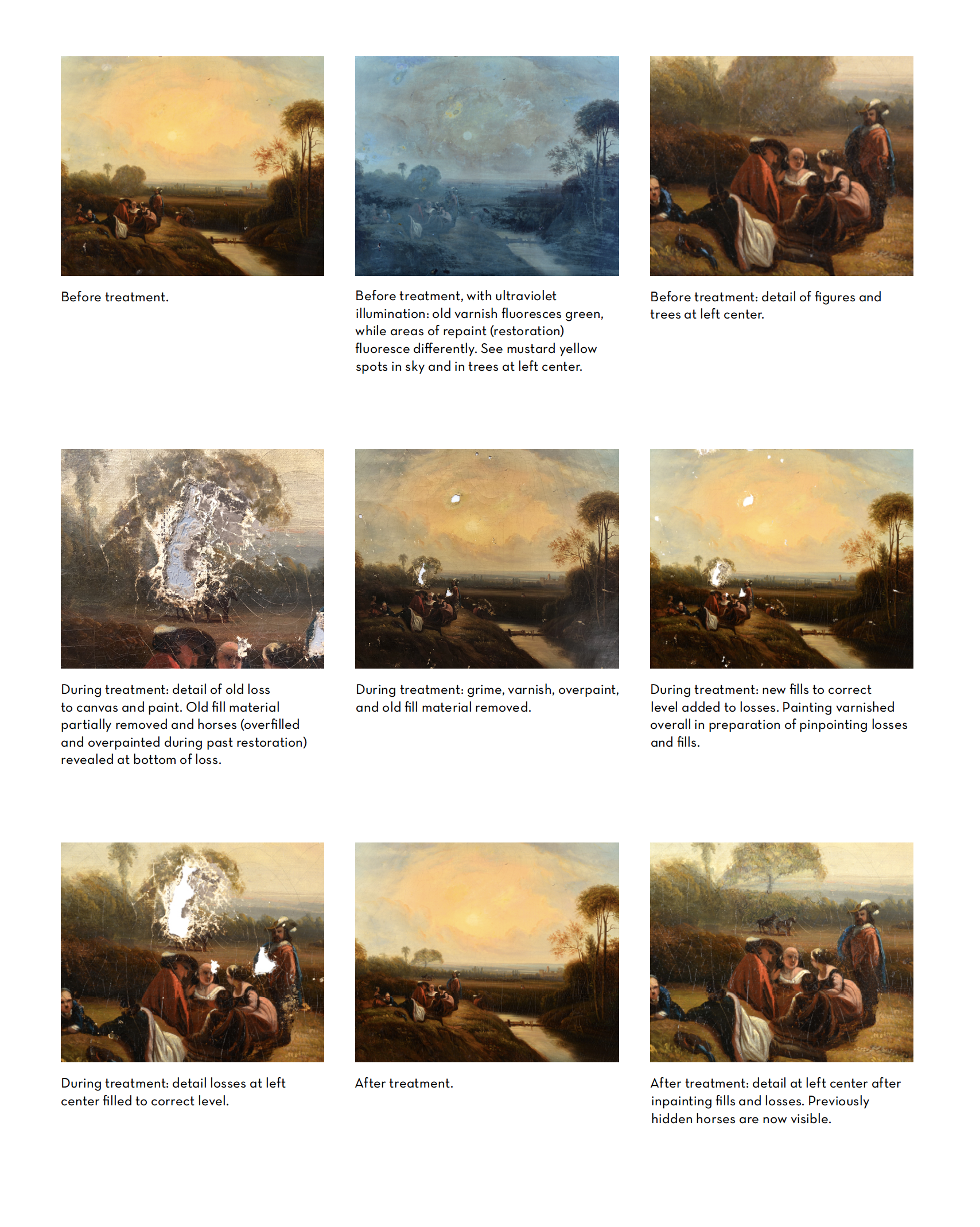

When working on a painting, the goal of the modern-day conservator is to restore a piece to as close to its original state as possible. One tool we use is inpainting: when time and damage has led to a loss of some aspect of the painting, you paint in the loss. But this hasn’t always been the case. In the past, conservators would create new art where losses had occurred, doing whatever it took to make the piece more ‘presentable,’ even at the expense of distorting the original artist’s intentions.

Several years ago, while working for the private conservation firm Page Conservation, I encountered an instance of inpainting that was quite thrilling. One of my favorite paintings I’ve worked on, titled Dutch Landscape, had been heavily—and poorly—restored, and during my treatment I found that the restorer had completely painted over two horses in the background. I think that whoever previously restored it didn’t know how to repaint the horses, so they expanded the trees. Viewing the work from afar, you wouldn’t notice, but on close inspection, you could see legs sticking out.

This type of discovery can really change how a work of art is studied. I’ve read about cases in which a painting has been read one way for hundreds of years, but with modern conservation techniques and tools, we can now see that it was heavily painted over in the 1600s. This can really shock people because they are attached to the current iteration of the work. It also raises conservation questions: Where do you take a piece back to—its utmost original? Or do you preserve the way it’s looked for the past 100 years because that is how viewers now understand it?

This is what’s so intriguing about working on paintings—people have been custodians of these pieces for hundreds of years, in museums, estates, and chapels, and they can be imprinted by that custodianship in interesting ways.

Unknown Dutch painter

Dutch Landscape

18th–19th century

Oil on canvas

13 x 16 in.

Private collection

Photos: Page Conservation, Inc.