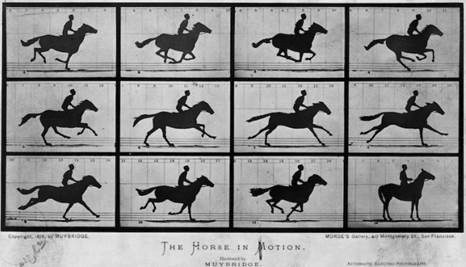

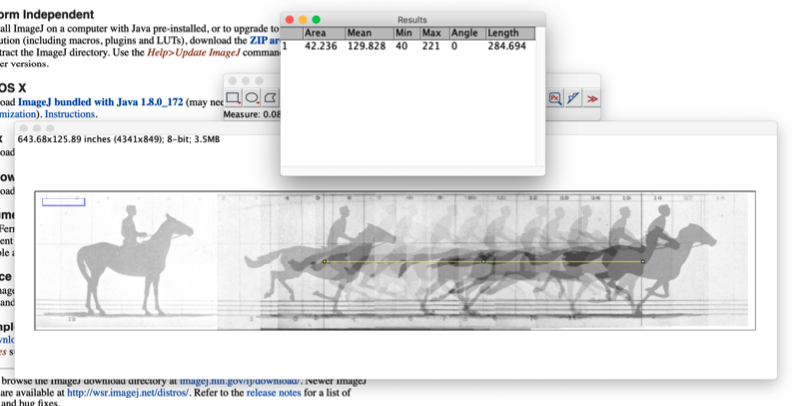

The photos look like a film strip: A silhouetted horse gallops across eleven frames before coming to a standstill in the twelfth. Numbers run across the top of each image, while vertical lines are visible in the background. Three of the frames show the horse’s hooves leaving the ground completely. The horse is 16 and 1/4 hands tall, Fletcher Jones Scholar in Computation and Visiting Assistant Professor of Media Studies Douglas Goodwin tells his students, the vertical lines are 27 inches apart, and each image was snapped with a shutter speed of 1/25 of a second. So, how fast was the horse running and how far apart were the cameras when these images were taken?

The students head into Zoom breakout rooms to discuss these questions. With the information that Goodwin’s provided—and some quick research to convert a “hand” into a more familiar unit of measurement—they determine that the horse was running at the approximate speed of a mile every minute-and-a-half, and that the cameras, like the vertical lines in the frame, were spaced at 27-inch intervals in order to capture the horse in different stages of motion.

The lab focusing on Eadweard Muybridge’s “The Horse in Motion” (1878) is just one of the methods that Goodwin has used to engage his computational photography class during remote instruction. Students have worked solo, collaboratively, and in one-on-one sessions with Goodwin to take photos, debate contentious ideas in the field, program unique images from scratch, and discuss the techniques used in the creation of “mystery photos,” or images made during the early days of photography. All these exercises align with Goodwin’s aims for the course: to help his students understand how images are generated from a computational and technical perspective.

“Right from the beginning of this virtual learning period, I thought about how I could work with students to create an academic experience that would be shared, but also personal,” he said.

In one such experience, students turned their rooms into pinhole cameras by covering windows with boxes and cutting a dime-sized hole for light to shine through. By adjusting the size of the pinhole, students learned how pinholes form images: A larger hole creates a brighter, lower-resolution image, while a smaller hole forms an image that’s crisper but dimmer. Ultimately, students used the pinhole technique to create upside-down, reversed images of the outside world, superimposed on the interior of their rooms like double exposures.

“I love photography, but I also love math and learning more about how things work,” said Zoe Schmitt ’23, who’s considering a major in mathematical economics and a minor in art. As a photographer for a music blog, she sees Goodwin’s class as applicable to her work: It’s taught her more about the ways in which cameras function, and the labs have allowed her to experiment with various techniques by building and using different photographic devices, such as the pinhole camera.

Roya Amini-Naieni, a Harvey Mudd College junior who’s majoring in mathematical and computational biology, described the pinhole experiment as “mind-blowing” and explained that Goodwin’s course has given her space to be creative and imaginative—including with projects she plans to pursue even after the semester ends. “I’m personally going to make pinhole camera curtains so that I can have a permanent pinhole camera effect in my room,” she said, adding that the process of creating these seemingly unreal photographs has been exciting. “It’s kind of like Disneyland!”

Goodwin also sent his students at-home photography kits, which included lenses, lasers, and cyanotype papers, which students used to create images of nature by placing objects on top of the papers and letting them develop. Since cyanotype paper is light-sensitive, covering parts of the paper allows the unexposed areas to remain bright while the exposed areas darken, ultimately creating an effect similar to that of a film negative. Mara Morioka ’22, a media studies major, said that this “supernatural” effect demonstrated the unreliability inherent in image creation: “We think of photography as a ‘truth-telling’ medium, but it can lie or be manipulated.”

The many steps in the cyanotype development process—from choosing the objects to arranging them on the paper to waiting for the image to manifest—allowed students to step away from and return to the Zoom classroom as needed, an important aspect of remote instruction. “I know students are spending a lot of time on Zoom,” Goodwin said, “so it helps to find activities that they can do in their rooms by themselves as much as possible.”

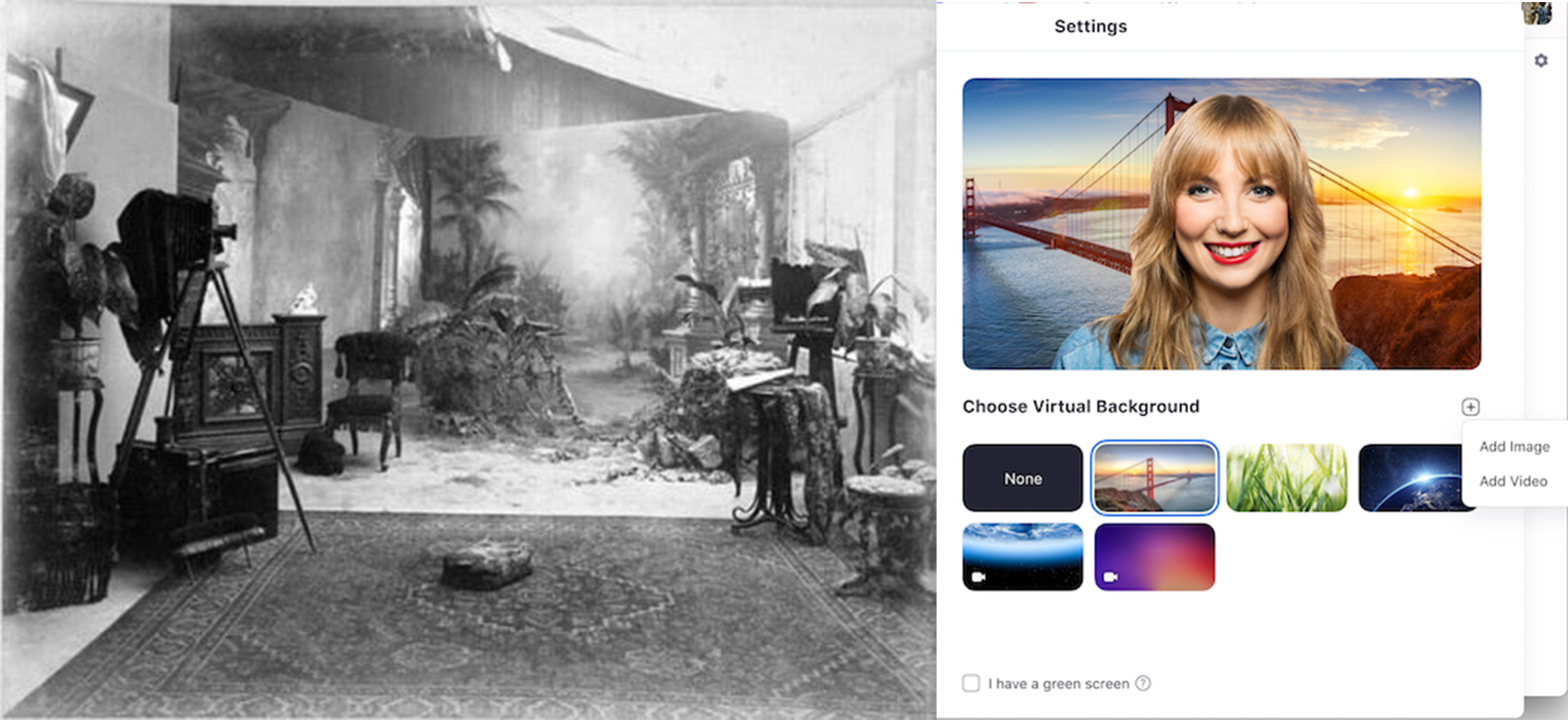

And although Zoom has presented its challenges, it’s ripe for meta-exploration in a class that examines the past, present, and future of photography. “I like to deal with the medium that we’re using, to think about its qualities and what it’s doing to our concept of images,” Goodwin said.

In fact, Zoom images fit rather neatly into the history of formal portraiture and photography. Zoom’s recommended lighting set-up replicates the lighting recommendations of historic photo studios, and virtual backgrounds have become today’s equivalent of nineteenth-century studio photography backdrops, which featured bucolic scenery. Even Muybridge’s iconic composite of the galloping horse, with its grid of images, is reminiscent of a Zoom screen.

“One of the things that’s really charming about Zoom is that we can look back and see how it fits into this history,” Goodwin said, noting that echoes of the program’s gallery format can be traced all the way back to Early Renaissance triptychs and altarpiece paintings. “In those paintings, there’s a tension between individual perspectives and the whole piece. Zoom has a similar quality, which creates its own tension.”

For Schmitt, it’s been interesting to think about Zoom not just as an educational tool, but as a tool that shares traits with other forms of art. “Just like with photography,” she said, “we have control over what we show others.” And for Amini-Naieni, the remote instruction experience has revealed a world in which mundane materials—from recycled boxes to dishwashing soap to lemon juice—can be used to create powerful images no matter where students are located: “Ultimately, allowing students to explore computational photography and art in their own environments lets them take that perspective anywhere.”