When Scripps announced in early July that remote instruction would continue for the fall 2020 semester, faculty expected that there would be challenges in conducting classes through online platforms, but also opportunities to expand the idea of what a liberal arts education could look like. Now that the fall semester is underway, Scripps professors have risen to those challenges and opportunities, creating courses that are flexible, creative, and student-centered.

“We don’t have to teach in the same way we always have,” said Jennifer Armstrong, associate dean of faculty and professor of biology. “Yes, it’s different, but this new online system gives you the freedom to try more creative, collaborative education. It’s trust-based pedagogy—students can take learning into their own hands.”

While the phrase online semester may conjure images of Zoom screens and laptops, remote instruction and learning isn’t exclusively tied to technology. Many of Assistant Professor of English Michelle Decker’s assignments encourage students to engage in creative, analog, offline activities. “Students need to learn while moving their bodies away from screens,” she said. “Reflection and creativity happen best when students are given the opportunity to move from passive to active learning.” For example, she designed an activity for her poetry class that instructed students to take a walk outside without their phones, find an object, and write a short poem or descriptive paragraph on the object’s tactile features, while also reflecting on the sensory experience of the walk.

To assist faculty in building robust remote courses like Decker’s, Scripps hired Nora Scully as an instructional design consultant in July. Scully, who has 15 years of experience in virtual learning and instructional design, said that a good online course typically requires about 50–100 hours of planning, so the sudden transition to distance learning in March presented challenges for professors accustomed to in-person teaching. She offers one-on-one sessions to faculty to help build their curricula and think through their pedagogy. “Often, they already have ideas, so what we’re doing is having a dialogue, filling in the blanks, and building solutions together,” she said.

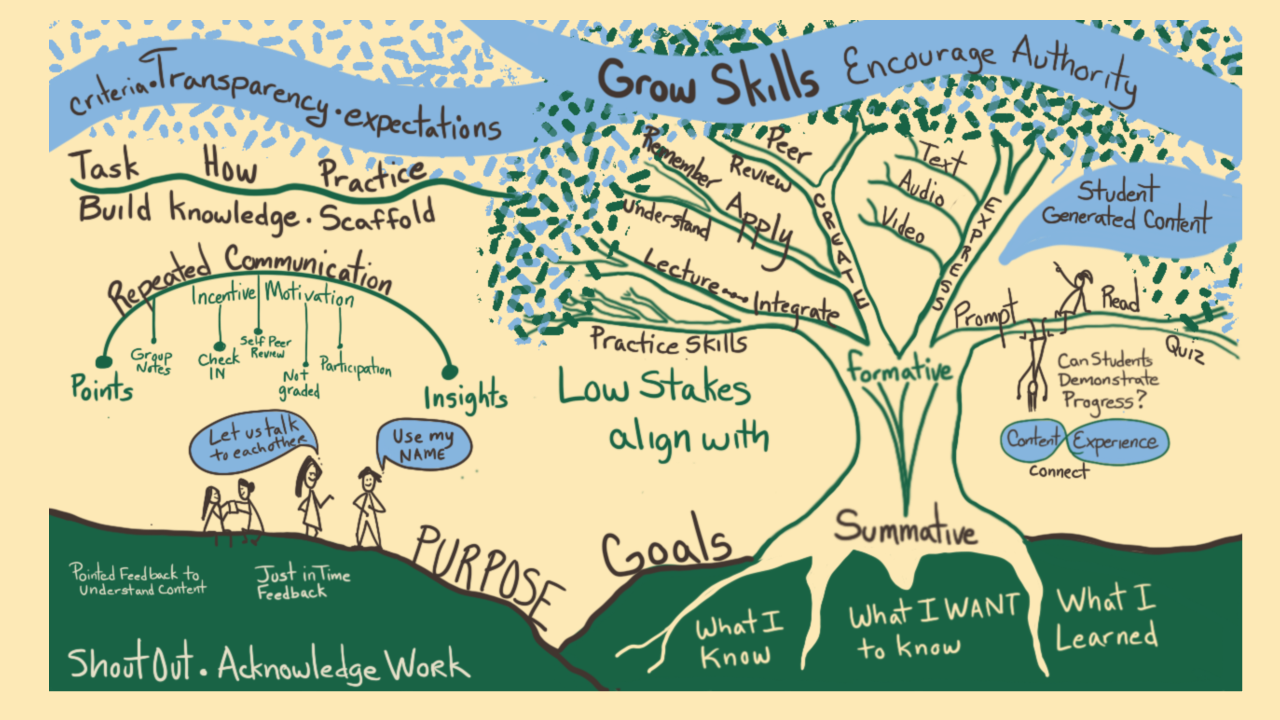

The Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) at The Claremont Colleges has also provided a number of resources for 7C faculty, including a self-paced workshop on teaching summer courses, downloadable course templates, and a series of modules on strengthening community for new faculty members. While their spring workshops focused on what CTL Program Director Jessica Tinklenberg called “pandemic triage”—recognition of the challenges brought on by COVID-19—transparency, communication, and care for students’ well-being have remained at the forefront of the CTL’s best practices for remote instruction in the summer and fall. Tinklenberg noted that the ongoing nature of the pandemic, the fight for racial justice, and the West Coast wildfires have all taken a toll on The Claremont Colleges community, and the CTL has hosted seminars on trauma-informed pedagogy and humanizing teaching and learning.

“Strengthening community has emerged as a theme for our teaching and learning workshops,” Tinklenberg said. “In creating strong online instruction, we have to foreground transparency, start from a position of care, and engage in intentionally equitable communication practices. Students need to see a clear path to success in their online courses, and we have to make sure that students get access to courses in a variety of ways.”

For chemistry lab coordinator Sadie Otte, that means providing flexibility with due dates, an explicit explanation of the extension process for late work, and weekly videos summarizing the previous week’s assignments, as well as upcoming activities and due dates. Mindful of students’ varying levels of access to materials, Otte has also provided creative options for in-home “kitchen chemistry” experiments, utilizing common household items. Earlier this semester, her organic chemistry students focused on chromatography and recrystallization, two different lab techniques for separating mixtures into components. Depending on the materials available to them, some students chose to use Kool-Aid, Crystal Lite, and food coloring to conduct at-home chromatography, while others used water and sugar to conduct recrystallization.

Decker has similarly adjusted the number of required readings on her literature syllabi and built small group, collaborative activities for students to maintain asynchronous connections. “The best thing we can do for students right now is to provide a flexible structure for learning that maintains standards but is also attuned to the challenges of an online semester,” she said. “Students want to learn, but since our [on-campus] community isn’t intact, we need to respect individual limitations.”

Thoughtful procedures like Otte’s and Decker’s are part of what Scully refers to as “the ethics of care,” a best practice in humanizing learning, whether online or on-campus. Scully noted that many of these practices, such as designing a well-organized course or engaging students in collaborative thinking, aren’t new—they just need to be adapted for a digital environment. “All this work is student-centered,” she explained. “Faculty are open to student feedback, and they’re willing to pivot and do what needs to be done in order to connect their students to their teachers, to each other, and to the world.”

Indeed, Otte said that the most vital aspect of strengthening her classes’ sense of community has been incorporating students’ voices and choices into the curriculum wherever possible: Her students have chosen their own course objectives, classroom values, research projects, and presentation topics. “It’s something I started doing even before we went online, and now it’s more important than ever,” she said.

Support for remote instruction will continue throughout the fall semester, as faculty continue to adjust their teaching to students’ needs. The CTL will offer a series of lectures on creating anti-racist pedagogy in the classroom—another cornerstone of their resources—as well as regular presentations on best online instructional practices. (The CTL provides the faculty who give these lectures and presentations with stipends that, in pre-pandemic times, were earmarked as course activity grants for faculty to improve classroom practices.) Decker and Otte will each present their best instructional practices in CTL workshops this semester, focusing on the two-pronged approach of creativity and care for students—now and in the future. “Small, project-based assignments enable students to see this strange time as not simply a hardship, though it is,” Decker said. “But it’s also an opportunity to start building the community and the world they wish to live in, even as we study the very real structures of violence and oppression that harm minorities and people of color especially.”

Scully believes that the strength of the Scripps community has bolstered faculty’s ability to adapt to the challenges of remote instruction, allowing them to translate what’s worked in the classroom to online interactions. “Courses at Scripps have a good student to teacher ratio, so faculty have the opportunity to be connected with their students—and they are so connected,” she said. “They care passionately about their teaching practices and their students.”