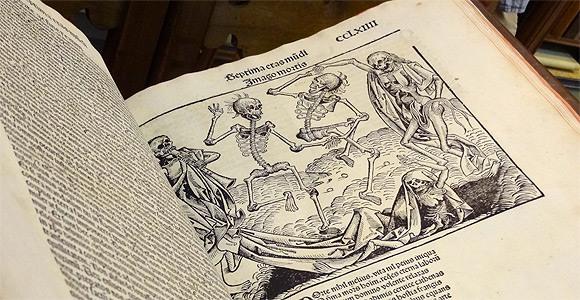

After over two years of conservation and restoration, the Nuremberg Chronicle has returned to Scripps College’s Ella Strong Denison Library. The chronicle, one of approximately 400 surviving Latin copies, was published in 1493 in Nuremberg, Germany and is also known as “Liber Chronicarum” (“Book of Chronicles”) from a phrase in the introduction.

The book is a biblical paraphrase of world history with much of its own. Famous as one of the best documented early printed books, over 2000 copies were printed in both Latin and German.

Holly Moore, the Head of Conservation at the Huntington who spent the past two years working on the book, sees and feels this history on every page.

“I always get a kick out of the fact that the paper is not the same from leaf to leaf,” Moore said. “Some are really thin and some are thick. There’s not much uniformity, but I like that about it, because it allows you to imagine how it was made.

“There was a huge run of these… I imagine a small shop trying to keep up with the run and not paying attention to how much pulp they put in the press,” Moore continued. “There’s a charm to it.”

Moore was careful to conserve this charm and the “human element,” as Judy Sahak, the director and Sally Preston Swan librarian for Denison Library, described it.

“The important thing is, does it compliment the original well?” Sahak said. “Is it in the spirit of the original?”

As a result, Moore was gentle in her cleaning of the pages, washing each leaf three times in filtered water. However, Moore chose not to buffer the pages, because “I didn’t want it to look too clean or it loses is soul,” she said. “It should look like a book from 1493, not fresh off the print.”

As part of this effort, much of the original damage of the book remains visible, such as water damage. In addition, Moore was also careful to make many of her additions – such as repairing torn corners – apparent as distinctly new.

The process of repairing corners involved placing each leaf on a light box and overlapped the weak edges with very thin Japanese tissue. To do this, she had to go past the weak area of the page and use up to six different sheets of tissue. She toned this tissue so it didn’t detract from the feel of the book, especially in the opening pages, but purposefully left the strengthened sections a lighter shade than the original leafs.

This style of work emphasizes conservation over restoration, a frequent debate in the art world. To honor the original work, Moore’s adjustments are both temporary (they can be reversed) and are clearly not part of the original book. The purpose, as Moore phrased, is not to make the book look new, but to make the book stable.

Feeling the leafs to note the difference between thickness which still remains, Sahak noted the pages are “so strong. It’ll last another 500 years.”

One part of the book that was changed dramatically is the cover. The previous cover was ripped and stained, described by Sahak as “nasty” with “crumbly leather binding and some tears.” While the library still owns the original cover, Moore redid the binding with new calfskin.

Even in this aspect the spirit of the original text was preserved. Moore both plaited the edge of the end bands on the cover and decorated the spine with a pattern typical of the time. Moore also bound the book with the technology they had available in 1493, including hand making linen thread cords that don’t require any adhesive or glue because it interlocks itself. By binding the book in this style, the edges are uneven, just as they were before restoration.

In addition, the end papers on the inside cover were custom made for the chronicle. Moore designed them by looking at a swatch book and requesting the thickness of one swatch, the color of a second, and the tooth (or texture) of a third.

Moore believes the book has been repaired before, but because of the continuously improving science of the industry, she had to redo much of the work.

“On tears, there was a chunky grain adhesive” that made the pages stiff, Moore said. “The leafs bend so much better now, they fall and drape. The health of the leafs is so good now.”

Moore worked on the book in her free time over the past two years, finally hiring an assistant in the final months to complete the conservation. At the end of the process, the book spent near four months just sitting under weight, adjusting to the changes that had been made and giving the pages time to shrink back down after being washed.

Now that the chronicle is back in good health, light pencil page numbers are still visible in the corners of each leaf. Moore sketched these because the page numbers in the original text are often unreliable, and she just didn’t get around to erasing them. However, the Denison staff don’t think they will erase the markings either.

As Sahak simply put, “It’s part of the history now.”