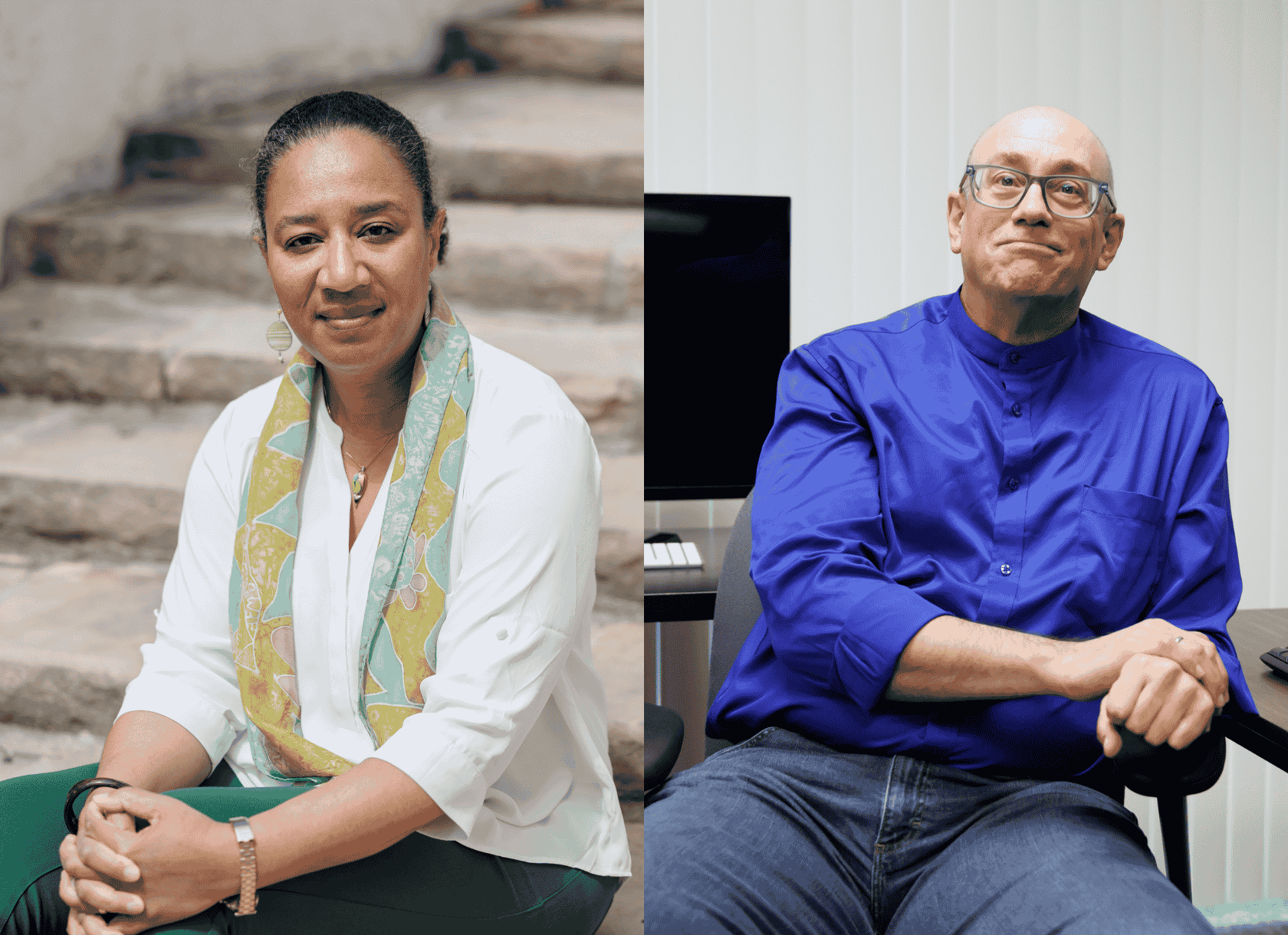

Professors Myriam J.A. Chancy and Michael Spezio

By Madeleine Nakamura

Originally published in the spring 2024 issue of Scripps magazine

The COVID-19 pandemic has been devastatingly transformative. In addition to the loss of countless lives—a toll which continues to grow—and the long-term health impacts some survivors of the virus are left with, many changes stemming from the pandemic are here to stay for the foreseeable future. Norms in healthcare, the workplace, and education have been irrevocably altered by COVID, and the full impact of the pandemic has yet to fully play out: these cascading echoes have an exceedingly long tail.

A commonly held attitude, whether spoken aloud or left implicit, is that COVID is now behind us—that because vaccines are available and our major institutions have made adaptations to account for COVID’s ongoing presence, the pandemic is a thing of the past. However, while drastically reduced, infections and deaths continue at a rate that must be taken seriously. The shifts in how our society operates have been made, and we can only look forward.

In higher education, addressing the reality of what teaching looks like after lockdown requires creativity and foresight. A core tenet of education is the promotion of flexible thinking and the development of skills that allow for adaptable problem solving; to survive, institutions of higher learning must model this adaptability from the top down. As the people responsible for educating students, faculty members like Hartley Burr Alexander Chair in the Humanities Myriam J. A. Chancy and Associate Professor of Psychology, Neuroscience, and Data Science Michael Spezio are at the forefront of navigating new classroom dynamics.

Conversations about institutional adaptations to COVID following the zenith of the pandemic are often dominated by a concern for high-level details. When discussing the economy, people want to know what corporations will do with office buildings that go unused due to the rise of remote work; in the educational sphere, frequent questions include how to ensure academic integrity in an increasingly digital classroom or whether asynchronous learning should be encouraged.

These details matter, but as Spezio points out, the human core of the issue shouldn’t be overlooked in higher education.

“During COVID, one student told me that both their parents lost their jobs, so they needed to work almost full time outside the home washing dishes and delivering food while maintaining a full course load,” Spezio says. “What a thing to carry—and many of our students carried similar burdens. Although being home is wonderful and family can be the fullest source of joy in life, a busy home does not always allow quiet spaces and resources for extended time thinking, reading, and writing.”

The Ripple Effects of the Pandemic in Higher Education

In turning to the logistical challenges they face now, institutions must take a multidimensional view that acknowledges the importance of health and wellbeing. As educators address the academic consequences of lockdown and attempt to anticipate continuing fallout in coming years, mental health is one of the primary concerns.

“There are data suggesting that the social isolation of remote learning, together with strains caused by sick loved ones during the heights of the pandemic, contributed to increased mental health symptoms among a range of age groups across educational levels,” Spezio says. He believes that institutions of higher learning will need to prioritize mental health and learning support through at least 2029 and possibly beyond.

Adapting to COVID more successfully in education also means learning from the pandemic and planning, Spezio adds. “I’m concerned that not enough is being done across all institutions of higher education and elementary and secondary schools to prepare for the next pandemic.” He emphasizes that to improve structures for online learning and develop safer in-person learning conditions to assist with other pandemics that might occur, institutions must work with students, families, and governmental departments.

The need for these efforts isn’t limited to any particular discipline; it’s vital that representatives from every field assist in developing more effective ways of conducting remote learning. “We need all of the disciplines involved in this conversation, since each discipline has unique perspectives on and educational requirements for learning,” Spezio says.

The structure of a philosophy class might require different considerations in remote learning than a chemistry class, and to build a functioning system, both should be considered. Speaking from her perspective in the humanities, Chancy says, “The ability to operate on many different fronts of communication from the written page to social media is a must, as is the ability to interface with others in hybrid forms. For someone like me who works across multiple geographies, hybridity has been a plus rather than a hindrance. Perhaps there has been less face-to-face, but there has been a vast increase in networking and getting to know people beyond the local space, which we should all be doing.”

Leaning Into Change

While COVID has caused educational damage that requires addressing, faculty members continue to take advantage of opportunities for growth, pedagogical refinement, and technical advancements. It’s become clear that remote learning, under the right circumstances, can serve as an equalizing force, increasing educational accessibility—for instance, by easing the financial burden of housing costs or by providing students with disabilities more options in their learning. “We should recognize that tools such as Zoom have enabled us to bring more people into classrooms and events than ever before, increasing diversity and plurality of perspectives in the classroom space,” Chancy says. As the world’s adjustment to COVID’s presence continues, educators are identifying key strategies and tools they want to prioritize.

For Spezio, these priorities include “open lines of communication, inquiring about where students are in their learning, connecting them with support such as the College’s Writing Center, making sure that electronic materials are available, recognizing student achievement in learning, and celebrating when students reach new levels of insight and novel ideas.”

In terms of new additions to his teaching methods, Spezio adds, “One of the new pedagogical and technical tools I’ve developed in my teaching is social annotation. I can annotate a PDF document for a course such that any student in that course opening any version of the document can see my annotations and place their own questions and perspectives in that document. I’m able to see those and tailor my teaching to students’ individual concerns and questions and perspectives.”

Chancy’s classroom adjustments have largely focused on new integrations of technology. “I have increased my knowledge and use of multimedia technologies in my teaching. I found that there were advantages to platforms that had been underutilized until that point, such as Canvas and Zoom. Canvas has proven to be a pliable tool where, as an instructor, I can provide more tools for students, such as external resources, PDFs of reading materials, and complete instructions for assignments.” In terms of providing opportunities for connection into the classroom, these technologies remain relevant: “Though we teach over Zoom less than before, it is an ideal tool for bringing guests to the classroom more frequently, particularly authors who may be in other countries.”

However, Chancy notes that in her experience, the benefits of these platforms have now regressed to a degree. “I have found that, over time, students are less inclined to consult those resources and to be active in Zoom classes. When it was the only way to teach, I found that students—particularly shy students and students of color—were more willing to be vocal and to interact in Zoom classrooms than in person.” It’s worth investigating this disparity, she suggests; perhaps there are lessons to be learned by examining how the usage of these platforms shifted between then and now.

Learning how to read and conduct in-depth analysis is one way to balance the barrage of misinformation; students who develop research and critical thinking skills will have a distinct advantage in the coming times – Professor Michael Spezio

In taking the measure of the current educational and professional landscape, both Chancy and Spezio identify a need for critical thinking skills and a mindful approach toward holding conversations with others. Chancy says, “The reliance on proficiency in technological tools, especially social media, is increasing rather than decreasing. At the same time, overuse of social media and online platforms without critical acumen have decreased everyone’s ability to employ critical thinking skills. Learning how to read and conduct in-depth analysis is one way to balance the barrage of misinformation; students who develop research and critical thinking skills will have a distinct advantage in the coming times.”

In Spezio’s view, “The skills anyone needs depend on the aims they have in view. If I were to say something general, however, I would point to the importance of listening, thinking carefully to understand what is being said before and in the process of criticizing it, and responding thoughtfully without reacting in a biased manner.” Navigating today’s thorny maze of disinformation and polarization requires “avoiding criticism for the sake of criticism and engaging in critique for the sake of learning and understanding, staying away from beliefs centered on gossip and ridicule, and never assuming that the categories one’s society or small social ingroup uses to label persons ever reflect the full truth about anyone.”

At a more fundamental level, when it comes to making their way in this newest iteration of an always-evolving world, students and graduates in any discipline share a fundamental priority: maintaining community. In the absence of connection, there can be no growth and no movement forward. Spezio believes a crucial element of this pursuit is “affirming and accepting that everyone is different but not lesser, that diversity recognizes individual difference and embraces it.”

Not every person, and not every institution, can be counted on to do the same. However, all individuals have the opportunity to choose to turn toward each other rather than away—to, Spezio adds, “not live or work in narrow self-interest but to live in hope, and to seek community with those who strive to transcend baser social tendencies.”