Scripps Professor of Art Ken Gonzales-Day’s exhibitions have been described as not to be missed, and he has been commended with numerous awards and accolades over his career. This past spring, Gonzales-Day was honored with a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship.

Gonzales-Day was one of 173 fellows selected from a pool of approximately 3,000 applicants working in various fields related to the arts. Guggenheim Fellowships are intended to fund blocks of time during which recipients can work with as much creative freedom as possible. Gonzales-Day will use his grant to take some time off from teaching to focus on his art practice, photo-based conceptual projects that explore identity and the construction of race. With his work included in five exhibitions opening this fall, he says that the timing of the grant is auspicious.

“It’s a great honor,” says Gonzales-Day, who has taught courses in studio art, photography, the Core Curriculum in Interdisciplinary Humanities, and art history at Scripps. “One of my photographic heroes, Edward Weston, received [the Fellowship] when he was about my age.” He goes on to describe how Weston used his fellowship to photograph the American West for a year, creating iconic images in the process.

Gonzales-Day began his career as a painter, but found that he could better explore the social and political issues he was interested in through photography. He enjoys the “indexical” relationship of photography to the real—the fact that photography is not representational, like painting, but records objects as they exist. In his Scripps courses, Gonzales-Day says he emphasizes the power of images and tries to make students aware of the opportunity photography provides as well as the artist’s responsibility in creating images.

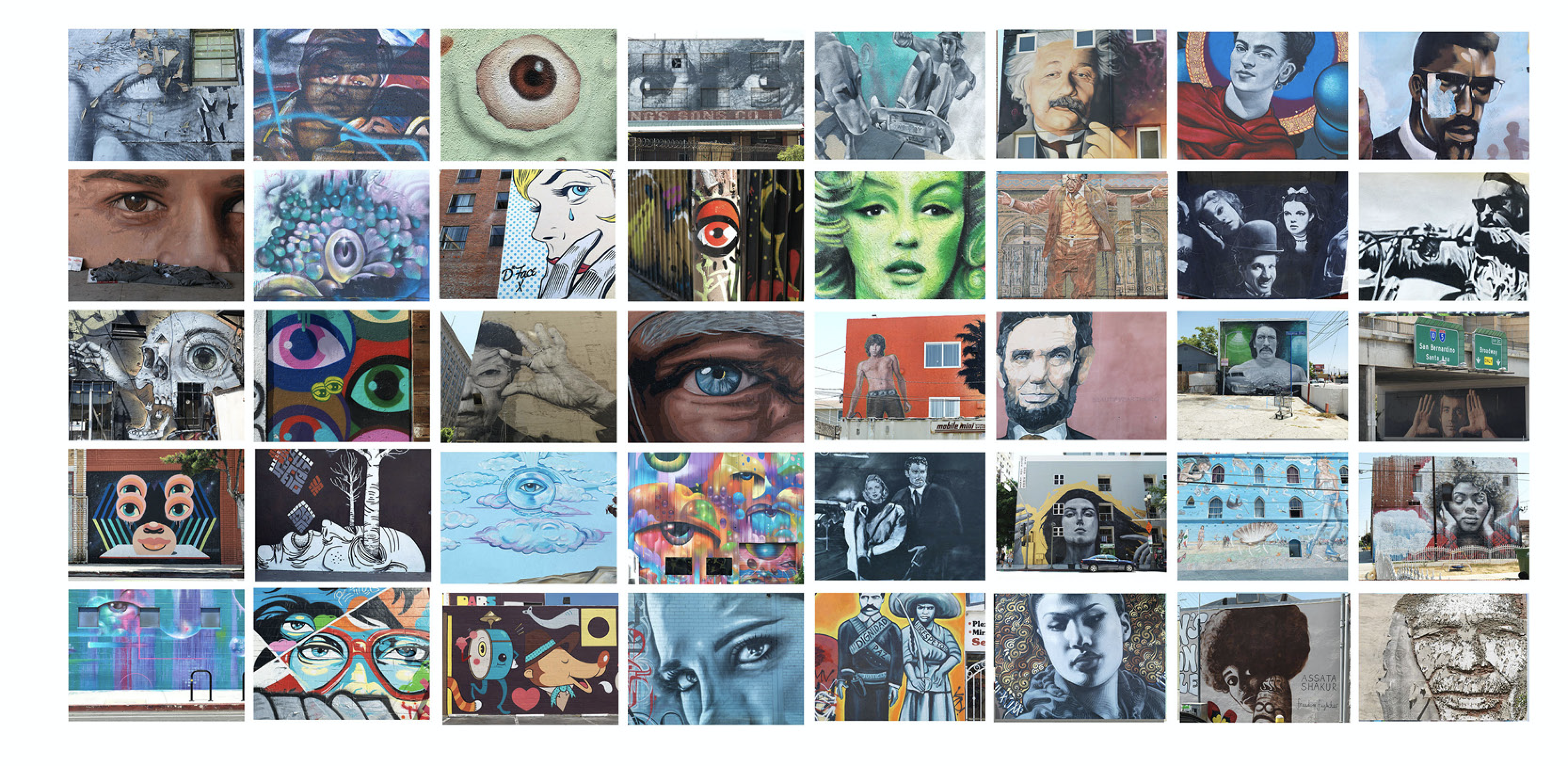

A recent body of photographs are the subject of his exhibition “Surface Tension: Murals, Signs, and Mark-Making in LA,” a project that doubled as the artist’s proposal for the Guggenheim Fellowship. Opening in October at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles, the exhibition is part of the Getty Foundation’s Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA project, which explores Los Angeles’s dialogue with Latin American and Latinx art. It was the Skirball that first contacted Gonzales-Day, expressing a specific interest in exploring the tradition of murals in both Latin America and Southern California. Interested in the idea, he embarked on a journey across Los Angeles to photograph the city’s murals as well as urban graffiti and markings that are not typically considered as art. The resulting photographs are a record of the visual language of Los Angeles’s many distinct communities.

“I think of [photographing Los Angeles] a little like if I was photographing different sides of a sculpture. [The city is] just a very big sculpture, so each part may be a little bit different, and it also becomes a kind of a data set,” he says.

Interestingly, some of the murals may have ceased to exist in the time between the photographs were made and the exhibition was installed. “The landscape of the city is always changing because it’s contested space, or in some cases private space, so the question of privacy, private land, public speech, and self-expression [are also at play].”

Taken together, the photographs reveal the city as a “representational system,” he adds, a theme that connects to his larger art practice. For Gonzales-Day, photography itself is a representational system; the content of the photo has a meaning, the photographer has a motivation or context that is brought to making the image, and the means by which the photo is displayed affects its reception. These factors work together to influence the way the audience interprets images.

Two of Gonzales-Day’s notable past projects, Erased Lynchings and Hanging Trees, utilize photography as a representational system to trace the history of race, racial violence, photography, and Mexican American social and political experiences. For Erased Lynchings, Gonzales-Day took photographs from 19th- and early-20th-century lynching postcards and other source material, where he then removed the victim and rope from each image. He explains that the viewer’s attention is then turned to the crowd of perpetrators, the role of the photographer, and the resulting impact of flash photography in that moment. For Hanging Trees, Gonzales-Day searched for and photographed lynching sites, some specific and others less exact, based on accounts describing them in relation to other landmarks.

The series of images resulted from six years of research into the largely unpublished history of lynching in California from 1850 until 1935, a timespan that begins slightly prior to most academic scholarship on the topic. Gonzales-Day began his research by exploring the NAACP and Tuskegee Institute records of 25 and 50 cases, respectively, in California. He also combed through newspaper archives of Los Angeles, San Francisco, Sacramento, and other metropolitan areas in an effort to determine dates and locations of lynchings that were not previously recorded. Over the course of his study, Gonzales-Day compiled a list of more than 350 lynchings that had occurred between those years in California.

Gonzales-Day unearthed in his research the preponderance of certain ethnic groups victimized in the state’s history of lynchings. “One of my primary discoveries was that in California, Latinos were the largest lynch group—and that’s a history that is unknown.” Specifically, Native Americans, Chinese, Latinos (of Mexican descent), and African Americans account for the majority of the total case list, he adds. “Most people think of the Wild West as the context for race-neutral, white-on-white violence. Two thirds of the persons lynched were persons of color, which means that race is a factor that had not been historically recognized.”

Gonzales-Day says his interest in this history of race and violence is in part drawn from his own experience as a Mexican American. But he is also motivated by his observation that there remains a need for more study on this grievous subject.

“Photographs are another way of thinking and another way of expressing these issues, but it’s no less critical or analytical than any text, essay, or other kind of scholarship.”

Along with his fall show at the Skirball Cultural Center, Gonzales-Day will also use his Guggenheim Fellowship grant to commence work on a large-scale solo exhibition at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., scheduled to launch in March 2018. In the solo project, he will examine how the U.S. has physically represented Native Americans through finding and photographing the castes, sculptures, and other physical materials depicting Native Americans at the Smithsonian.