By Rachel Morrison

Douglas Goodwin has always been fascinated with how time, context, and perspective shape our conception of reality. His first encounter with this phenomenon occurred when he returned to his hometown of Caldwell, New Jersey (featured in the opening credits of The Sopranos), after a 10-year hiatus. He had grown a foot between the ages of 10 and 20, and when he visited the house where he had spent his childhood, he had a radically different experience of his body in space: whereas once the house had seemed big, now it was impossibly small. “This betrayal of my own perception and perceptual system challenged the notion that anything could be objectively ‘true,’” Goodwin recalls. Nothing has been the same for him since.

This fall, Goodwin joined the Scripps College faculty as the first Fletcher Jones Scholar in Computation. A scholar, creative programmer, video artist, and systems architect (he is responsible for the computer networks that undergird the first online university, the University of Colorado’s Virtual Campus, launched in 1997, as well as the user interface of the Los Angeles Metro), Goodwin is guided in his research by an important question: How do language and other technologies mediate our perception of reality?

Goodwin plans to teach courses that examine the trajectory of photographic technology, including computational photography, as well as alternative and analog “non-binary” computation and cybernetics. One of his primary aims, however, is to teach students to develop

a better understanding of cameras and computation and to establish a new relationship to images.

“We are experiencing a crisis of representation,” explains Goodwin. “Photography used to be a simple process of fixing some light in a dark box. Now, some cameras can make pictures entirely by synthetic means.” Consider the current phenomenon of deepfakes: the manipulation of images, audio, and video, via artificial intelligence and machine learning, in order to create footage and photographs of politicians and private citizens engaged in false—and oftentimes damning—acts. While this type of manipulation may seem to be a modern phenomenon, it is in fact as old as image-making itself.

“There are parallels between these new techniques [for synthetic image-making] and early photographic manipulation,” Goodwin says. Though not all image manipulation is nefarious, it nonetheless has the capacity to undermine the fealty of images as objective representations of reality. To illustrate this point, Goodwin takes readers on a tour of this phenomenon throughout image-making history, showing that to see may not be reason enough to believe.

Here Be Fairies

A photograph taken by Elsie Wright in 1917 shows her cousin, Frances Griffiths, visited by fairies.

In 1917, 16-year-old Elsie Wright and nine-year-old Frances Griffiths convinced the British public that they had been visited by fairies. The cousins had produced a series of five photographs that showed the fairies sitting with them near a stream in Cottingley. Although there was a healthy amount of public skepticism, there was also a surprising amount of belief in their veracity, partly because of the British fascination with the supernatural in the wake of World War I. This was bolstered by the fact that photographic manipulation—and the ability to spot it—were not yet a part of cultural literacy.

“These images are not convincing today because we know how to spot this kind of photographic manipulation,” says Goodwin. “It’s easy to see that these fairies are just paper cutouts placed in the foreground of the shot. But although this image may be patently false to our contemporary eyes, we need to continue developing critical looking practices as manipulation techniques and technologies evolve and become more sophisticated.”

Fallingwater

It’s all in the angles: Shown here is a wide view of the living space at Fallingwater, emphasizing expansiveness, versus a photograph of the same room composed to emphasize intimacy and calm.

Around the same time that Goodwin realized that he had outgrown his childhood conception of home, he traveled to rural Pennsylvania to visit the Frank Lloyd Wright–designed house, Fallingwater. “As I approached the site, it became clear that I had been duped by all the photographs I had seen prior to coming,” recalls Goodwin. Wright, who stood 5 feet, 7 inches tall, designed Fallingwater to his own proportions. However, according to Goodwin, many promotional photographs depict the home’s interior spaces as palatial, rather than intimate, in scale. “These images serve more to promote a vision of the architecture and its influence than to describe real space,” Goodwin says. “The contradiction suggests propaganda.”

Synth or Cynth?

“[Modern] cameras have dispensed with a simple correspondence between subject and image,” says Goodwin. A smartphone photo, for example, is the result of highly orchestrated functions that improve the image, such as motion stabilization, color balance and brightness adjustments, refocusing, and other fixes. “Consumers love these features, and our enthusiasm for them clouds our judgment about how mannered and strange these images may appear in 20 years—much like the fairy photos from 100 years ago.”

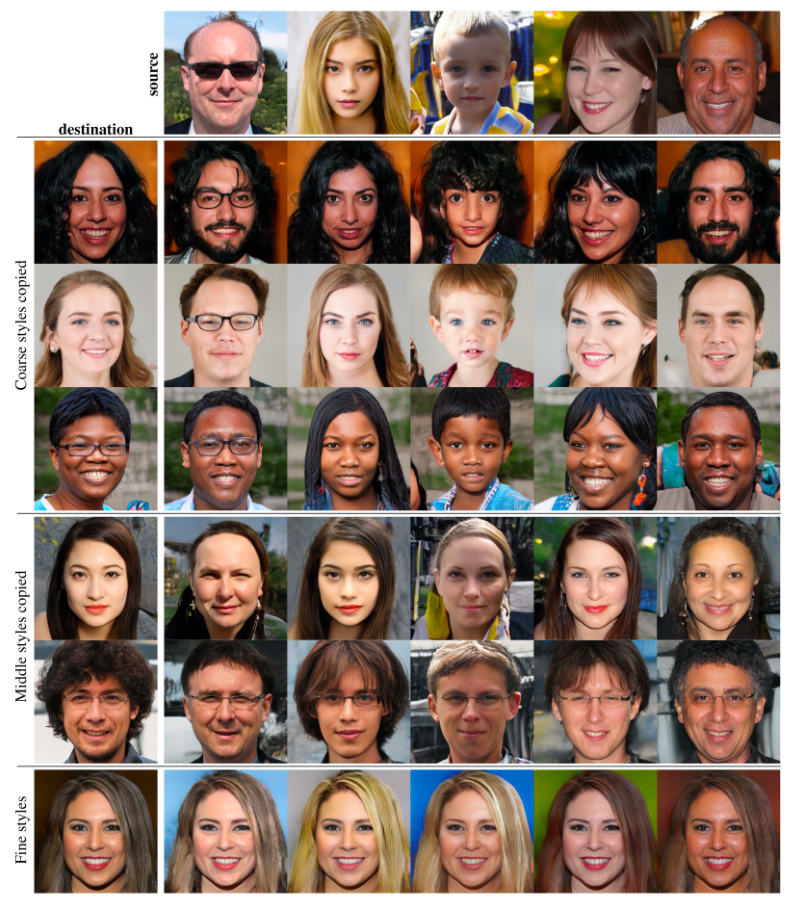

Further, as these images proliferate through social networks such as Flickr or Instagram, they enter a data set from which masses of synthetic faces may be created through artificial-intelligence neural networks. “I play a game with students called ‘Synth [synthetic] or Cynth [like “Cynthia”]?’ They have to guess which image is synthetic and which is real. It’s a trick question, though, because both images are synthetic. I want students to develop a critical viewing practice. Are we right to expect so much from photos? To admit them as evidence? And since computers are involved, why do we expect our machines and what they make to be impartial and objective? Because right now, the images pass, and we aren’t asking the right questions about them.”

Synth or Cynth? Can you tell which is the computer-generated image?

The images in the top row and far left column are of real people. The inner images are synthetic composites created by StyleGAN. This shows how data sets of real images are used in artificial-intelligence networks to create synthetic images.

Image republished from Tero Kerras, Samuli Laine, and Timo Aila, “A Style-Based Generator Architecture for Generative Adversarial Networks,” eprint arXiv:1812.04948 (2018), available at stylegan.xyz/paper.